Ana Enriquez & Tatum Lindsay

June 2014

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. It is a revision of “Understanding Judicial Opinions” by Ana Enriquez (2014). A PDF version is also available.

In CopyrightX, as in many courses at American law schools, most of the reading assignments will be judicial opinions. A judicial opinion is the judge’s explanation of her ruling and the reasoning behind the decision. Typically, a judicial opinion consists of a few components: the facts of the case, the applicable law, and the application (or analysis) of the law. At its heart, an opinion is similar to a scholarly essay or even a short story. However, like any genre, the judicial opinion has some unique and unusual characteristics. To understand opinions and use them as a tool for learning copyright law, it helps to know

- the role they play in the American legal system;

- where they come from; and

- how to read them.

In addition, this guide will introduce basic legal vocabulary and explain how the structure of American judicial system shapes laws.

1. Why Opinions Matter: Their Role in the American Legal System

The United States is a common-law jurisdiction, meaning that the overall framework of the U.S. legal system derives from the English common law. The distinguishing feature of a common-law jurisdiction is that judicial opinions are a source of law. Other common-law jurisdictions include the United Kingdom, India, and Nigeria. When judicial opinions serve as a source of law in a common law jurisdiction, they are sometimes referred to collectively as case law or precedent. Judges turn to case law to fill in gaps left by the other forms of law. Judges also rely on case law when the correct interpretation of a law is unclear.

The principle of stare decisis (Latin for “to stand by decided things”) guides the common-law judge, at least in theory. If a higher1 court that has the ability to review the judge’s decision has addressed an analogous situation, the judge must follow that court’s decision. When no court with the power to review the judge’s decision has addressed the issue, the judge may consider the opinions of other courts or even of scholars and experts, but he is free to disregard them.

Common law stands in contrast to civil law, which is a far more widely used legal system, exemplified by the laws of France, Japan, and Mexico. In a civil-law jurisdiction, judges do not create new law. In both civil and common-law jurisdictions, constitutions, statutes (laws created by the legislature), and regulations (laws created by the executive branch) are sources of law.

2. Where Opinions Come From: Civil Procedure and the Structure of the U.S. Courts

In the United States, each state has its own system of courts. There are also federal courts, which are not associated with particular states. Federal courts are the only courts empowered to hear and decide copyright cases, because copyright laws are federal.

2.1 The Timeline of a Copyright Infringement Case

Copyright infringement cases typically begin in federal district courts. District courts are the trial courts of the federal system. There is at least one district in each state, but some states are divided into multiple districts. For instance, New York is divided into the Eastern, Western, Northern, and Southern Districts.

Most copyright cases are civil cases—disputes between private parties (individuals, corporations, etc.). In some situations, copyright infringement gives rise to criminal liability. To meet the threshold for criminal liability in copyright cases, the defendant must commit willful copyright infringement for the purposes of “commercial advantage or private financial gain.”2 In such instances, government prosecutors can initiate a criminal prosecution. We will learn more about criminal liability for copyright infringement in Week 12. An important difference between civil and criminal cases is the procedure used to try those cases. Generally speaking, criminal procedure affords more protection to defendants, because more is at stake. In a criminal case, a defendant who loses may spend time in prison. In a civil case, the losing party will only have to pay money or refrain from certain actions.

In civil cases, the party instigating the lawsuit is called the plaintiff. A civil suit begins when the plaintiff files a complaint against the defendant, the party being sued. The defendant can respond in a variety of ways. She can file an answer, or if she thinks the plaintiff’s claim is poorly written, she can file a motion to dismiss. If she has claims to make against the plaintiff, she can file a counterclaim.

Then, the discovery phase begins. During discovery, which happens before trial, the parties exchange requests for information. Each side is legally compelled to comply with the other side’s request, so long as the requests fall within the procedural rules.

Also during the pre-trial period, either party can bring a motion for summary judgment. The party bringing the motion (the moving party) argues that the case can be decided without a trial. At a trial, the jury (or, if neither party has demanded a jury, the judge) would hear from both parties and decide matters of fact. If no material facts are disputed, the judge will grant summary judgment and issue a decision, deciding the questions of law. If the case goes to trial, the jury makes its decisions and then the judge decides any matters of law and issues a decision. The decisions of district courts are not considered precedential, so subsequent judges are not required to abide by them.

2.2 Appealing a Decision

When a district court issues a decision, the losing party is generally entitled to appeal that decision to a higher court.3 The person who appeals a decision is known as the appellant, regardless of whether he was initially the plaintiff or the defendant. The party opposing the appellant is the appellee. To appeal successfully, the appellant must convince the higher court that the lower court made an error. The higher court does not retry the case. Instead, it assumes that the facts determined by the fact-finder are correct, and it examines the decision for errors in the lower court’s application of the law.

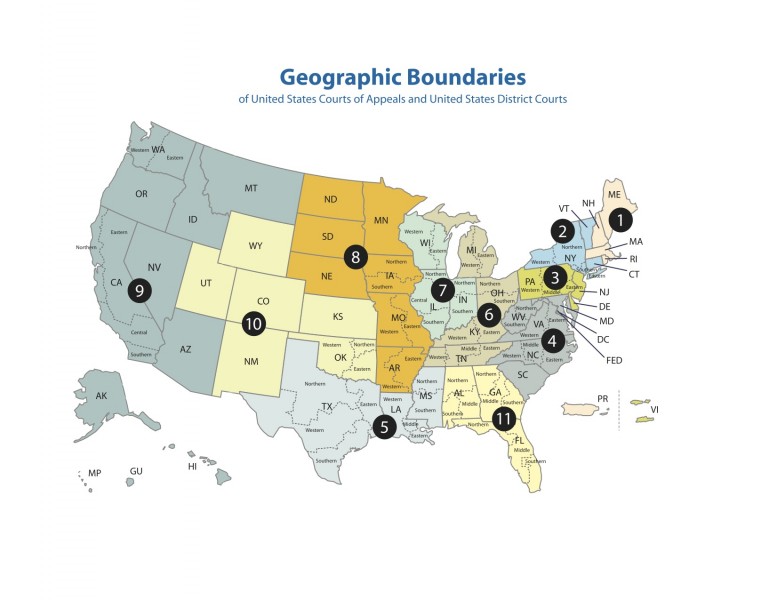

Courts of appeals hear appeals from district courts. There are 12 regional courts of appeals, one for each circuit or region of the country.4 Courts of appeals are sometimes called circuit courts or referred to by their circuit number (e.g., the First Circuit). Because the courts of appeals are regional, they tend to develop regional specialties. The Second Circuit, which includes New York City’s publishing industry, and the Ninth Circuit, which includes Silicon Valley’s technology industry and Hollywood’s movie industry, hear many copyright cases. For a map of the circuits and the districts, see the appendix to this document.

Typically, an appeal is heard by a three-judge panel. After hearing the arguments, the judges vote to decide how to rule. One of the judges writes an opinion explaining the court’s decision. If another judge disagrees with it, she may write a dissenting opinion explaining how she thinks the case should be decided. It is also possible for a judge who agrees with the opinion of the court to write a concurring opinion in which he expands on the court’s reasoning or outlines a different justification for the same outcome. If a party loses in the panel decision, it may petition the court of appeals to rehear the case “en banc,” meaning with a much larger group of court-of-appeals judges.

The decisions of a court of appeals are binding only on the courts within its circuit. For example, a decision from the First Circuit is binding in subsequent First-Circuit cases and in cases in the Districts of Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Puerto Rico, and Rhode Island, all of whose decisions can be appealed to the First Circuit (see appendix). A decision from the First Circuit is not binding in a case before the Second Circuit or the Southern District of New York (an inferior court within the Second Circuit), but judges in those courts can use it as a guide if they choose. As you can imagine, this can result in disagreements between the circuits. Such disagreements are known as “circuit splits.” The strange consequence of this is that, even though all of the United States is governed by a single set of copyright statutes, the judge-made law of copyright in New York is slightly different from that in California.

Decisions from the courts of appeals can be appealed once more, to the Supreme Court of the United States. However, unlike the courts of appeals, the Supreme Court is not required to hear all of these cases. Instead, the Supreme Court selects a small number of cases to hear each year—about 80. The Supreme Court grants a writ of certiorari (“cert”) in cases it decides to hear. In addition to hearing appeals from the courts of appeals, the Supreme Court hears appeals from the highest state courts and sometimes from other federal courts. The Supreme Court is most likely to grant certiorari if there is a circuit split or the case is otherwise of national importance. If the Supreme Court hears a case, its decision cannot be appealed. For this reason, it is called the “court of last resort.”

3. How to Read Opinions

Judicial opinions are typically presented in a way that enables the reader to glean a significant amount of information quickly. The caption, or name, of the case gives the names of the parties. For example, an important Supreme Court decision has the caption Campbell AKA Skyywalker, et al. v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. Acuff-Rose is appellee (and the plaintiff); Campbell is the appellant (and one of the defendants). The name also exists in shorter versions, such as Campbell v. Acuff-Rose. The shortest way to refer to a case is usually by the first word of the first party — in this case, Campbell.

Most published versions of cases also include the name of the court, the date of the opinion and, in appellate cases, the date that oral argument took place. In addition, if the case has been published, it will typically give its citation, a string of numbers and letters indicating the case’s location within a published book of judicial opinions. For instance, the citation for Campbell is 510 U.S. 569. This means the opinion was published on page 569 of the 510th volume of the U.S. Reports, a collection of U.S. Supreme Court opinions. Many of the cases we read in CopyrightX will come from the U.S. Reports or from the Federal Reporter. The Federal Reporter contains the decisions of courts of appeals and is abbreviated “F.”

The opinion will also typically give the name of the judge or justice who wrote it. In some cases, judges sitting together will decide not to reveal who wrote an opinion. In that situation, it will say “per curiam” (Latin for “by the court”) in place of a judge’s name.

The opinion itself is less predictable than this prefatory material, but usually contains the following materials: First, it is likely to include information about the case’s history and the stage at which it was issued. (For instance, the opinion might be written after a motion to dismiss, after a motion for summary judgment, or after trial.) This is called the procedural posture. The opinion will also typically include some information about the facts of the case. This is especially true for trial court opinions. Last but not least, the judge will usually state the legal issue(s) involved, her decision about the issues (the holding), and her reasoning.

Although all of these components are present in most opinions, identifying them is not always straightforward. A law student’s or lawyer’s goal in reading a case is to ingest the information quickly and, usually, to apply the reasoning to another case. One way to develop this skill is to “brief” cases. When a law student briefs a case, he typically identifies several pieces of information: the parties, the procedural posture, the facts, the issue, the holding, and the analysis. Although it seems foreign at first, identifying this information, understanding judicial opinions, and applying their reasoning to new cases becomes much easier with practice.

Additional Resources

Wex, a free legal dictionary and encyclopedia from Cornell’s Legal Information Institute

Orin S. Kerr, How to Read a Legal Opinion

How to Brief a Case, from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Robert Berring, Chaos, Cyberspace and Tradition: Legal Information Transmogrified

The Common Law and Civil Law Traditions, from the Robbins Collection

The Oyez Project, IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law

Copyright Information Center at Cornell University

Stanford Copyright and Fair Use Center

Appendix

From: http://www.uscourts.gov/uscourts/images/CircuitMap.pdf

1. The court system is conceived of in a hierarchy—trial courts are lower or inferior courts, while appellate courts are higher ones.↩

2. 17 U.S.C. § 506 (2012).↩

3. The exception to this is that the government is not allowed to appeal a not-guilty verdict in a criminal case.↩

4. There is also a thirteenth court of appeals, the court of appeals for the Federal Circuit. It hears appeals in certain types of cases, including patent cases and cases involving monetary claims against the U.S. government.↩